The One About the Falling Horses

On Animal Abuse in the Film Industry

CW/TW: graphic violence, animal cruelty, death and torture

Hey, Practitioners! Thanks for stopping by. Before we move on, I want to issue a warning. Today’s newsletter explores cases of animal cruelty and abuse, and some descriptions are quite graphic. As such, I advise you to read with caution. If you can’t stomach the subject matter, it might be best to skip this one entirely.

Watching harpoon after harpoon pierce through the mother’s thick skin, I cringed. She screeched, and I was compelled to cover my ears. She could have dodged the harpoons. But she had offspring to protect, and that restricted her movement. That’s why, among many, they had chosen her. The tulkun wasn’t real, but I could feel its pain. Why were those men so cruel to this creature, I asked myself, and immediately answered: because there was money to be made. The shot that went into its belly was lined with explosives. The mother was badly hurt, and she knew it. She struggled for a bit. Then she died. And I was left with a question.

For the most part, our mall trip had been worth our abandoned pajamas and blankets. We’d gone to see Avatar: The Way of Water. We were not disappointed. The lush, green vistas of Pandora were just as impressive thirteen years on, and the film’s message about man’s inherent kinship with nature and the urgent need to protect the environment from ourselves felt timelier than ever. But the movie left its mark on me for a different reason.

Around the story’s halfway point, as a ploy to draw our heroes out from hiding, the military bad guys from Earth team up with the maritime arm of the RDA (the NGO overseeing the mining of Pandora’s resources). It turns out this ragtag crew of fishermen, who are supposed to be studying Pandora’s marine fauna, are actually big game hunters. And they are hunting tulkun, Pandora’s approximation of humpback whales, in order to extract a valuable substance called amrita from their bodies. We follow the crew as they chase a mother tulkun, and after a tense, Jaws-esque confrontation, are treated to an inside view of her dead body. Watching this gruesome scene, I grimaced and drew back. And a weird idea came into my head. What if this was a real animal, and they’d killed it just so they could film inside it?

I couldn’t stop thinking about this idea for days. The idea that people, that we, would see living, breathing, innocent animals injured or killed to make a scene from a movie appear realistic. And on the heels of this initial thought came another. We’ve all seen movies which contain the certification “No Animals Were Harmed in the Making of This Movie”. If you’re like me, you’ve never paid much attention to this slogan, except for cackling at the memes it spawned over the years. It’s perfectly normal that an organization would exist to regulate the safe use of animals in movies, right?

But now I wondered. Why was this certification needed in the first place? After all, humans never certify things for no reason. Usually, it’s to keep the seller of a product from getting sued. Which means that at some point, something must have happened. Something that woke people up to what was happening on film sets, and brought about the need to reassure them again. I wanted to know how animals were being treated before “No Animals Were Harmed…” came about. And I needed to know if the slogan had made a difference.

So I fetched my detective’s hat and pipe and started to investigate.

Electrocuting an Elephant (1903)

It began with an elephant named Topsy. A circus elephant, she was accused of murder and sentenced to public execution by electrocution. On January 4th, 1903, people flocked to Luna Park in Coney Island to see the big event. An event organized by the Edison Manufacturing Company, no less. Whether Thomas Edison himself was involved has been a subject of debate1. We know he was not there for the execution itself, but still his name appears in the film’s initial screen, right underneath the title. The organizers did not fully trust the destructive power of alternative current, so before they hooked her up to the electric wires, Topsy was poisoned. Then, 6,600 volts went through her body.

She collapsed after 10 seconds. They called the film Electrocuting an Elephant, a most prosaic title. The whole thing was uploaded to YouTube in 2014 and since then, has garnered well over a million views. I don’t recommend watching it—it’s a horror show. But should you still want to, here’s the link.

Other than being a collection of moving pictures, Electrocuting an Elephant does not have much in common with “movies”, in a Hollywood sense. Topsy was not an actor, but an unwilling participant, and the objective of the picture was not to tell a story: it was pure, dumb spectacle, made to appeal to man’s most gruesome sensibilities. But don’t worry your pretty little heads. Because Hollywood too abounds with stories similar to Topsy’s.

Dig long enough, though, and you’ll find stuff that’s even worse. I will tell you two particularly shocking tales, because I feel that I must. But know that there are many, many more.

A warning here: the following few paragraphs are not for the squeamish or the easily disturbed.

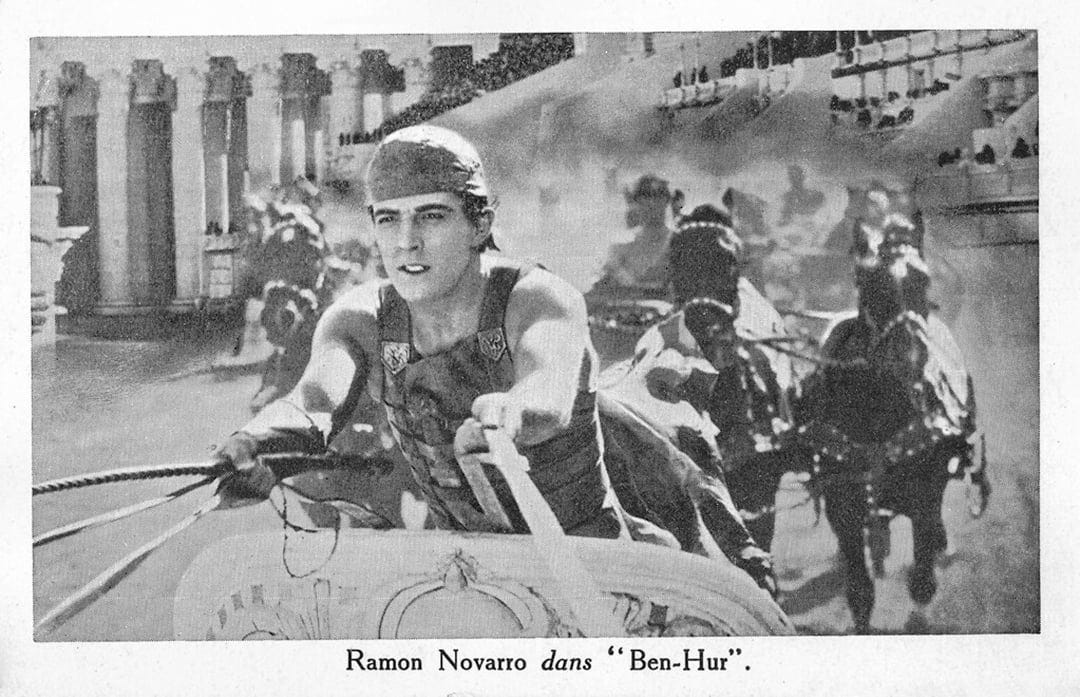

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

Based on the world-famous novel by Lew Wallace, this Fred Niblo-directed adaptation tells the sprawling story of a young Jew who was falsely accused of attempting to murder a Roman governor, and then enslaved by the Romans. To say Ben-Hur is epic in scope would be a gross understatement. Its 141 minutes are populated by a cast of over 150,000 people, and the story cycles through a variety of scenarios, from grand parades to daring sea battles. The film was marketed as “The Supreme Motion Picture Masterpiece of All Time”. I won’t debate that, but I hear the 1959 version was even better.

In any case, a staple of the Ben-Hur mythos is the massive chariot race, and it features extensively in both versions. To give you an idea, the 1925 crew used approximately 200,000 feet (or 61,000 m) of film to capture it. Everything was meticulously planned out over several months. Still, when it came to the safety of its crew, the team was willing to cut many corners. According to various reports, between 100 and 150 horses, as well as one stuntman, perished during the filming of the chariot race. Yes, you read that right. One human and 150 horse fatalities for a 9-minute scene. Most of the horses were injured during the race itself, and instead of receiving proper treatment, were immediately put down on the orders of the second-unit director, B. Reeves Eason.

Jesse James (1939)

Fast-forward to 1939. Before then, in spite of public outcry, animal abuse during film production went largely unpunished. For filmmakers, animals were little more than disposable props, unless they were especially valuable, like, for example, “falling horses” (stunt horses which could be trained to fall and get back up). But everything changed in ‘39. Why? Well, because a horse fell off a cliff. To be exact, because a horse was ridden off a cliff, on purpose, to make a scene look good.

It happened on the set of Jesse James, a run-of-the-mill western. Towards the end of the film, Jesse and his brother Frank are chased by an evil posse. With no other avenue for escape, they make a literal leap of faith and jump into a lake, taking their horses with them. The director wanted to show off. He’d get this scene just right, in one take. So, to make sure the horse behaved as expected, a sliding mechanism was set in place to trip it up. Horse and rider fell over 70 feet.

In one version of the story, the horse broke its back against the rocks.

In another, the horse did not die from the fall. Instead, touching the water, it went into shock, which rendered it unable to swim. For a while it thrashed about and then, exhausted, sank. The scene came out like the director wanted.

For the first time in history, public protest of the incident prompted the chief animal rights organization in the U.S. to intervene in a case pertaining to movies and television. American Humane, or AH for short, was established in 1877 as a coalition of 27 state-based humanitarian associations. Its chief aim was to protect farm animals against ill treatment. Eventually, its jurisdiction expanded to include child safety. Neither AH, nor any other humanitarian group had ever directly intervened on movie sets. But after Jesse James, AH took action and, in 1940, created its film and television unit.

That’s all for the history lesson. Now let’s try to answer some questions.

“No Animals Were Harmed in the Making of this Film”. We’ve all read it countless times, and never paid attention to it. I, for one, always took it for granted. Of course no animal was harmed in the making of this film. Are you nuts? Why would they be?

As we’ve seen, this kind of thinking is a mistake. Before 1940, animal abuse was long considered commonplace. That’s why I’m grateful for American Humane, even though they aren’t perfect. I couldn’t find the statistics, but I’d like to believe that cases of animal abuse have substantially decreased since 1940. According to their own data2, American Humane monitors over 70 percent of known animal action in film and TV productions. I’d like to believe that means they’re making a difference. I really do. Unfortunately, there are copious examples to the contrary.

It turns out “No Animals Were Harmed…” doesn’t necessarily mean that no animals were harmed. There are limits.

According to the Hollywood Reporter3, as many as 27 animals (including sheep and goats) perished due to malnutrition during the filming of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. AH did not investigate, citing that, because the alleged deaths occurred during a production hiatus, it lacked the proper jurisdiction.

As well, on the set of Life of Pi (it breaks my heart to share this, as Life of Pi is one of my favorite novels), a film in which the titular character not only becomes stranded at sea, but has to share his flimsy white boat with a Bengal tiger, the tiger (very much a real one, not CGI like I’d mistakenly assumed) nearly drowned. The film crew called him King.

You guessed it. In spite of everything, both films received American Humane’s certification.

Now, I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to live in a world where making great movies trumps protecting innocent animals. Animals who’ve got no business being in those movies anyway, except because we want them to.

I was bitten by a dog when I was little. Because of that, I was never very fond of dogs. I resented them as creatures with no moral compass, no guiding principles except their own hunger and killer instinct. But when my family decided to get a dog, I saw my misguided opinions for what they were: crap. Lifting him with one arm and painstakingly measuring a selfie angle with the other, I hugged that white furball to my chest. We became fast friends, and our friendship felt natural, organic. My fear of dogs dissipated as my love for them grew.

In the intervening years I met a slew of other dogs, as well as a few cats. I learned that a pet’s love for its owner is the purest form of love there can be. It’s unconditional, and altruistic. Animals demand nothing in return for their love, care, and company. The least we can do is take good care of them. Make sure they have access to quality food and water and regular appointments to the vet. And maybe find it in our hearts to reciprocate that love. And if we can’t do that, we should leave it to someone who can.

Reading through material to prepare for this issue, I remembered The Ivory Game, a documentary I’d watched a while before on Netflix. It’s about people who hunt African elephants to sell their tusks in China. Since 1500, the African elephant population has shrunk by 98%. And as the film’s title aptly points out, this all happened because of a game: the game of killing elephants to provide the rich with new trophies. That’s how the game of Hollywood works, too. They make movies to give us cool new stuff to watch. It’s all in the name of fun. And elephants, horses, sheep, goats, dogs, cats, chickens, and sea turtles die because fun is all we care about.

Why should animals be the ones to pay the price for our games?

Whew. Thanks so much for sticking until the end! I know it probably wasn’t an easy read, so I truly appreciate it. Maybe you can spare three more seconds to click on the 🫀 button below👇🏼 (it helps!)

https://edison.rutgers.edu/life-of-edison/essaying-edison/essay/myth-buster-topsy-the-elephant

https://www.americanhumane.org/initiative/no-animals-were-harmed/

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/animals-were-harmed-hollywood-reporter-investigation-on-set-injury-death-cover-ups-659556/

I hadn't thought about the Little Big Man incident in years. So I think I might write about it. Thank you for writing your post.

Back in college, a professor screened the movie Little Big Man, a revisionist (and great) western starring Dustin Hoffman. There's a horiffic scene in which the U.S. Cavalry is massacring men, women, and children in a Lakota Sioux encampment. During the scene, horses are also killed and many of the other students—all of them white—audibly reacted to the horse murders. There were gasps. I was taken aback by the reaction and chastisted my fellow students for reacting more strongly to the death of the horses than they did to deaths of the Indians. But, over the years, I've realized that the students were reacting to the real fear and potential injury of the horses. The horses didn't know they were in a movie. Of course, the actors knew they were acting. The stunt people knew they were stunt-acting. I don't know that the other students were conscious of why they reacted so strongly to the horses' deaths. But I think that it's far more difficult to suspend one's disbelief when it comes to animals in films, especially when we're talking about the days when animals weren't protected at all in moviemaking.