Fury

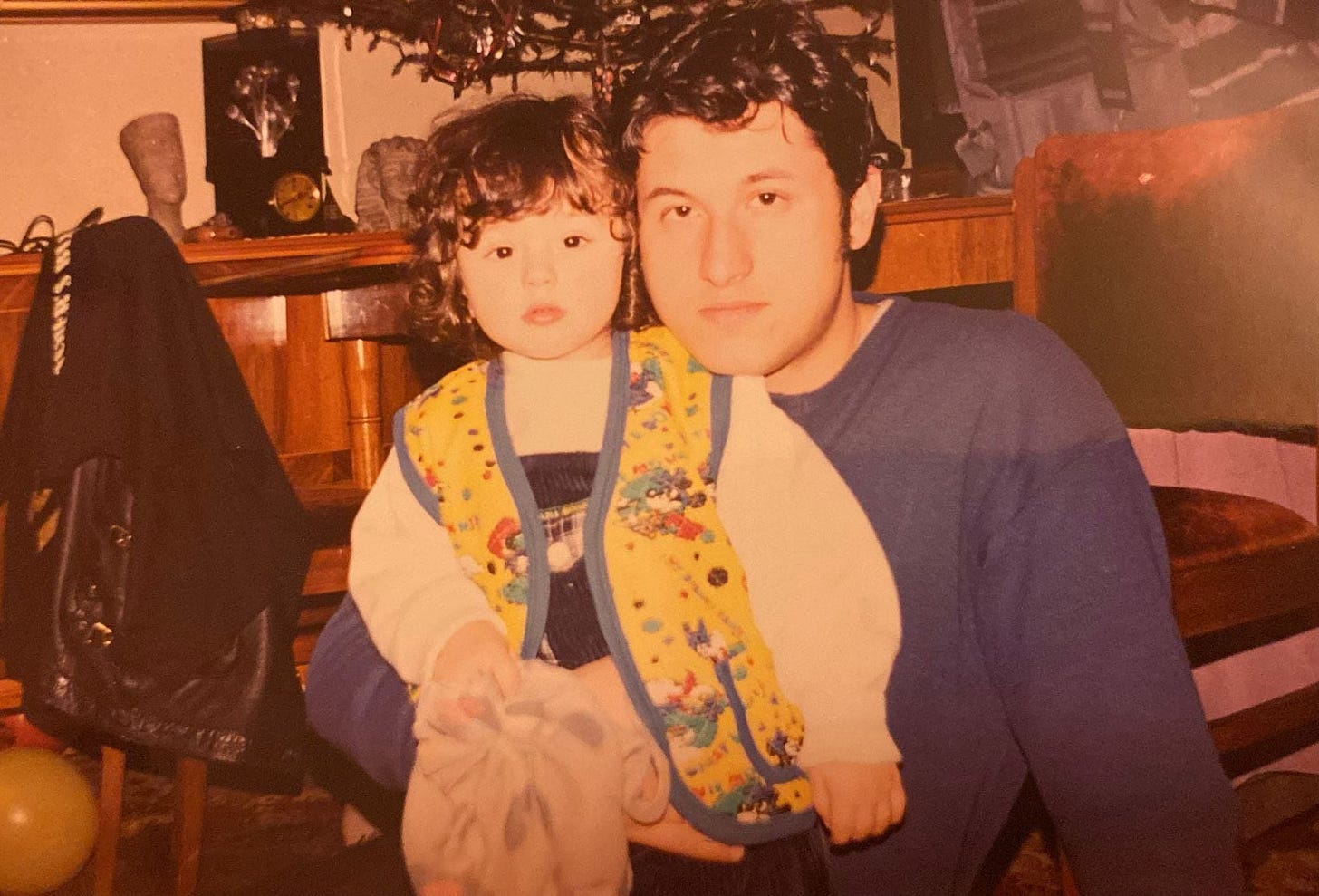

A True Story of Fathers and Sons

Hello, dear readers. This piece was first published in the CoAuthored newsletter by the folks at Foster, upon which I cross-posted it here. I want to make it a full blown post, though, because I think it deserves to hang with the greats. For those of you who weren’t here the first time, buckle up. It’s about to get intense.

(Also: the piece was reprinted in the third issue of The Raven’s Muse, a small and dandy literary magazine. COOL!)

Sometimes, because he didn’t know how else to connect with me, my father took me walking. One night, when I was around six, we found ourselves in front of an arcade. Framed by dozens of blinking monitors, I witnessed this place I’d only known from screens similar to its own, this holy hall of portals to alien worlds, where the boy with the quickest finger was king. My body thrummed as I stepped in. By the light of the screens I saw boys, of all ages, engaged in private battles. This place radiated masculine energy, but not the kind that I was used to. This was no locker room, no football field, no dojo—places where I’d failed to prove myself before. As the crying boy in front of me dragged himself away, my feet moved and I found myself replacing him in front of a game called Soul Calibur II. My fingers probed buttons arrayed in a pattern that was new to me yet felt no less familiar because of it, and I begged my father for a coin, half expecting a refusal on the grounds that video games did not give you bigger muscles, but this was our bonding night, so he assented. Electronic music filled my ears and drew a crowd of boys like bats to my location. They watched as I selected my fighter, a warrior encased in crystal who looked nothing like me. Then a boy to my left came close, got on his tiptoes and whispered into my ear. I bet you won’t get past the first fight. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. My fingers clenched and I could feel it, rising to the surface. Anger, that monster which possessed all in my family, reared its boil-infested head. Who did this kid think he was? Images of my father from previous days floated into my mind. Him clutching the steering wheel with fingers white as pixie dust, and muttering under his breath swear words he thought I couldn’t hear or at least understand. Him, red as a lobster in a checkout queue somewhere advancing slower than osteoporosis, waiting for his turn to have his order messed up by an incompetent employee, and, minutes later, yelling in said employee’s face when they invariably did. To understand my father back then, think of Mark Ruffalo’s Hulk. Though mostly kept in check, his rage was always there, a cobra coiled to strike. You never knew what’d set him off, and once the wick had been lit, waiting it out was all you could do. But I didn’t see my father’s rage as something to fear. I longed to be like him, this strapping, valiant young man who’d had a hand in birthing me. I gazed down at the kid, and imagined punching him to the ground, smashing his face against the unforgiving concrete and, in my victory, stepping on his neck, all while my father watched, raptly, proudly, from the shadows. My face broke into a smile. The stage loaded and two angular warriors manifested on screen. I won the first fight. And the next one. And the next several. The crowd had packed closer together, fencing me in, and the boys were no longer silent now but chanting, not my name, as I’d have liked, but the name of my character. Siegfried, Siegfried, Siegfried. When I reached the penultimate stage the bold boy came forward again. No one’s ever beat this one before! What makes you think you will? That was it. My lungs filled with air. The world became a frenzy of artificial light and sound as I turned in the boy’s direction. Shut up, you schmuck, I bellowed, can’t you see I’m better than anyone here? And he did. The boy shut up. And I understood why my father screamed all the time. It was what you did if you wanted to be heard. Taxi drivers, cashiers, doctors, teachers, all had muck in their ears and the only way to remove it was to shout it off them. It didn’t dawn on me until many years later where my father’s rage—where all men’s rage—comes from. On the way to the car we were silent. Why wasn’t he showering me in laurels? I’d done what he’d wanted, hadn’t I? So why wasn’t he seeing me? But you know, dear reader, I think my father saw me, all right. More than that. For the first time in his life, I believe my father saw himself. This was a man who’d gone from one trap to another. The trap of a tyrannical father. The trap of soul-suckingly steady work as a salesman for a multinational company, which he eventually quit to start a successful small business, only for the 2008 recession to smack him back to kitchen-sink reality. The trap of no longer being the main breadwinner of the family. The trap, perhaps, of children. My father didn’t rage because he felt powerful. He raged because he felt weak. He raged because of, not in order to. Which brings us back to me. From the day of my birth, people had been confusing my gender, thinking because of my pretty eyes and small nose and soft skin that I was a little girl. My father showed indignance whenever it happened; but what if it secretly gave him hope? Hope that I would not be so easily perturbed. Hope that I’d be the one to break the cycle. Hope, I say, that I would not become him. That night, he saw a side of me neither of us knew existed. Is that why, from then on, he began to pull away from me? So that I did not turn into just another man? Another bitter, angry, desperate man? If that’s true, his plan backfired, for I would spend the next two decades reaching for his shadow.

This is beautifully written, Andrei! I grew up with my dad and brother from when I was 9 onwards and I understand so well the pain, anger and desperation of men.

A super essay.